Information

Composer: Gustav Mahler

CD1:

- A Talking Portrait: Bruno Walter in Conservation with Arnold Michaelis

- A Working Portrait: Recording the Mahler Ninth Symphony (Narrated by John McClure)

- Symphony No. 9 in D major: I. Andante comodo

- Symphony No. 9 in D major: II. Im Tempo eines gemächlichen Ländlers (Etwas täppisch und sehr derb)

- Symphony No. 9 in D major: III. Rondo-Burleske (Allegro assai. Sehr trotzig)

- Symphony No. 9 in D major: IV. Adagio (Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend)

Columbia Symphony Orchestra

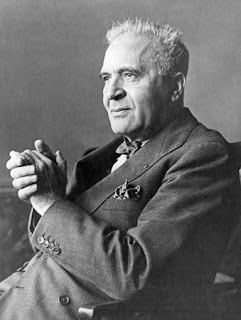

Bruno Walter, conductor

Date: 1961

Label: Sony Classical

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Review

"... The first stereo recording of the Ninth was made in 1961. The conductor was the man who had given the first performance in 1912 a year after Mahler's death and who had also been responsible for that first "live" recording in Vienna in 1938: his friend and disciple Bruno Walter. In his Indian Summer in California, Walter recorded the Ninth with the orchestra of Californian players assembled by Columbia and this is the version most Mahlerians of my generation learned the work from. In its present remastered edition on Sony (SM2K 64452) it includes the wonderful rehearsal sequences that made up the third LP in the original three disc set and which had disappeared in all subsequent LP re-issues. Narrated by producer John McClure, this is a crucial document in the recorded history of Mahler's music and should not be missed. The same can also be said of the symphony recording for it's the same grand tradition represented by Horenstein's though, of course, much better recorded.

Walter's conception of the first movement is on the same scale as Horenstein though he's more hesitant at the opening, elegiac, valedictory. Impressions that will persist throughout. This is a perfectly valid view for music that explores aspects of death and farewell and must have been somewhere in Walter's mind at the time since he was turned eighty when the recording was made. Often you hear him depicted as a "softer-grained" conductor than many colleagues. To an extent this is true, especially when considering later recordings, but in no sense should it be viewed as a pejorative attribute. Listening to recordings made earlier in his career will tell you that even this probably had more to do with the development of the serenity that sometimes comes with age since the younger Walter was capable of furious accounts of music that other colleagues would send you to sleep with. This was never more so than with his first recording of the Ninth, as we will find out. In this second recording there is nothing blunted about the way he sifts the strange sounds at the opening of the development. Indeed he seems all too concerned to bring out the peculiar quality of Mahler's late style: rasps from muted brass, ghostly taps from the timpani. Maybe there are times when the tempo drops below Andante, but it's quite marginal. His stress on elegy and valediction, as compared with Horenstein's greater drama, can be perceived in the treatment of the falling "Lebwohl" motive which seems to turn the key of the movement for Walter whereas with Horenstein it's one among others. Both take the long breath, both are unerringly aware of structure in the way men of that generation were, but Walter brings out the more autumnal colouring, the softer shades, the mellower sound palette, where Horenstein seems more concerned with marking contrasts. For example, the muted trombones at the centre if the development don't "tell" as much as they do with Horenstein, they are more integrated into the texture. Likewise the cracks from the timpani at the climax of the movement, where death's annunciation on trombones blazes out in the opening arrhythmia, hit much harder under Horenstein. This is emphatically not a question of Walter softening the music then. Rather it's his way of shading what is there with greater stress on lyricism, mellower contrasts, maybe at the expense of some drama. The recapitulation resumes the mood of valediction and how moving is the long dialogue between the solo horn and flute that leads us into the coda where Walter's concentration never flags.

Walter is splendid in the second movement also. In the rehearsal sequences we hear how John McClure had to plead with him not to stamp his foot in time with the landler and how, at the start of the movement in the finished recording, he wasn't successful. (Walter stamped his foot at exactly the same point in the Vienna performance twenty-three years earlier.) The attention to detail in this movement is wonderful, as is the attention to any music that shows kinship to the "dying fall" "Lebwohl" material in the first movement, notably in the Tempo III slower landler material. As would be expected, Walter also appreciates the need to delineate these three tempi one from another giving each dance a separate character that, when they combine, produce a mesmerising "dance-requiem". Not least the closing pages, so carefully rehearsed by Walter as you can hear in the rehearsal sequences, that simply breathe character from every pore.

The Rondo-Burlesque third movement is a deal smoother than with Horenstein and others, so there's not as much "Sehr Trotzig" as might be hoped. I admire Walter's slightly more measured tempo, however. At this speed there's plenty of opportunity for the excellent woodwind players to chatter, giggle and unsettle in music that's more than just an empty showpiece. There is less of the cumulative build than with Horenstein, though. The "Music From Far Away" episode is pure and refined but, crucially, filled with nostalgia. Even if this does meant Horenstein's menace is missing it makes its effect.

Walter was never a believer in stretching the fourth movement on the rack, sometimes to the music's detriment. In his 1938 "live" performance he delivered what is the quickest performance on record and even in 1961 the emphasis is on fluidity with perhaps some loss of emotional power and the kind of Zen-like stasis that can be generated in certain parts by some conductors, not always with conspicuous success. With Walter this is the nobility of farewell, more reconciled with the inevitability of death and leave-taking, and I think it suits the rest of his conception for all my niggling reservations. There certainly is much to move and impress, not least the last climax which has more than enough weight and power. A pity, perhaps, that Walter didn't linger more over the closing pages, keeping instead a single-minded concentration to the end just as he did in 1938. What we have is a perfectly natural and satisfying conclusion. All in all, this is one the greatest recordings of the Ninth - lyrical, nostalgic, valedictory, autumnal, expressing the mood of the conductor, playing up one aspect of the composer's conception in this late work. Where Horenstein seemed to be constantly asking the music questions, Walter seemed to believe he had most of the answers already. The playing of the Columbia Symphony is exemplary even though these musicians don't perhaps have the feel for the idiom their Vienna colleagues of 1938 had. The recorded sound is a rich and detailed balance, if a little weak in the bass and prone to a slight fizz at the top. Only four double basses were used which rather surprised Bruno Walter but this, according to McClure, was enough for the acoustic of the hall used. ..."

-- Tony Duggan, MusicWeb International

More reviews:

http://www.amazon.com/Mahler-Symphony-No-9-Rehearsal/dp/B000002A7K

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Gustav Mahler (7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was an Austrian late-Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th century Austro-German tradition and the modernism of the early 20th century. In his lifetime his status as a conductor was established beyond question, but his own music gained wide popularity only after periods of neglect. After 1945, Mahler became one of the most frequently performed and recorded of all composers. Mahler's œuvre is relatively small. Aside from early works, most of his are very large-scale works, designed for large orchestral forces, symphonic choruses and operatic soloists.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustav_Mahler

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustav_Mahler

***

Bruno Walter (September 15, 1876 – February 17, 1962) was a German-born conductor, pianist and composer, widely considered to be one of the great conductors of the 20th century. He left Germany in 1933 to escape the Third Reich, settling finally in the United States in 1939. He worked closely with Gustav Mahler, whose music he helped to establish in the repertory, as an assistant and a protégé. Mahler did not live to perform his Das Lied von der Erde or Symphony No. 9, but his widow, Alma Mahler, asked Walter to premiere both in 1911 and 1912. Walter's work is documented on hundreds of recordings made between 1900 (when he was 24) and 1961.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

FLAC, tracks

Links in comment

Enjoy!

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteCopy Adfly (adf.ly/XXXXXX) or LinkShrink (linkshrink.net/XXXXXX) to your browser's address bar, wait 5 seconds, then click on 'Skip [This] Ad' (or 'Continue') (yellow button, top right).

ReplyDeleteIf Adfly or LinkShrink ask you to download anything, IGNORE them, only download from file hosting site (mega.nz).

If you encounter 'Bandwidth Limit Exceeded' problem, try to create a free account on MEGA.

CD1

MEGA

http://adf.ly/1MnrS3

CD2

MEGA

http://adf.ly/1MnrS5